Screenshot from 2012-08-11 22:37:33

So I’ve been interested in distributed computing for some time, since 2007, basically around the time I started doing web development. I’ve always sort of romanticized the notion of distributed computing because of its vast theoretical potential. Projects like BOINC, SETI@Home and Folding@Home have always given me some kind of idealized notion of “computing for good”, inspiring some kind of useful social, scientific or otherwise beneficial change to humanity. But those projects never got the kind of adoption which could truly change the world, together they form networks which are specialized but can, in the end, only eke relatively minute performance.

Part of the problem lies in their intrinsic forbidding voluntary nature. It takes too much effort to install and amplifies the problems intrinsic to any “democratic” system: why bother? Voter apathy often stems from a feeling that an individual contribution regresses towards nothing, which is statistically certainly true, but never helpful if it plays a part in the participation of one of these collective entities.

In a broader sense, I’ve always suspected that part of what is necessary for technological progress is the loss of control. Certainly something which appears true from a human experience, that the vast arrays of neurons bound by a cranium are uninviting and wholly unwilling to expose their inner raw computation power to the emergent conscience within them. No doubt the human brain is good at computing, just not (as it appears) math, but intuition (especially of the physical kind) can only arise when a system internalizes some very complex math. We just can’t access it, because evolution or some other process has determined that it was something that had to be done away with on the climb to higher cognitive powers.

Likewise, I think computers are convergent in that sort of way. There’s a great ladder of abstraction which is growing taller and taller, a tower of babel of sorts, and at the end, perhaps we’ll find a similar goal, maybe not of god per se, but an equally sought target of consciousness or some other high level intellectual faculties contemporaneously denied to computers.

Part of this is losing control, which is inevitable and politically dangerous. Computing terminals are powerful and capable of much more than they’re being used for. In fact, most computers spend most time idling, the processors get ever faster not for the handling of the idle time but in order to smooth out the few bursts that actually require fast computation.

It’s impractical for operating systems to build into them some kind of distributed computing platform, however ideal that would be. It’s too contentious to ever get adopted, conceptually a short step away from the ability for a mega-corp to pilfer your precious information as well.

But the browser, specifically the web, provides us with an interesting opportunity. Here, we have significantly less fear of personal privacy, since it comes with an expectation of sorts for information sharing. The existence of client side scripting and its prevalence gives an implicit permission to exploit system resources during the site’s tenure.

Now, of these granted permissions, we have the freedom now to exploit in order to create something truly remarkable. Because it’s not so much voluntary on the part of the user, so much as voluntary on the part of the site maintainer who now has the responsibility of allocating and managing the system resources of his visitors, for their brief but additive virtual encounters. The users lose control, and that’s a good thing.

Old Stuff

When I first wrote that introduction, I mentioned that I was interested in distributed computing for quite a while, and that’s true. 2007 was, at time of writing five years ago. A bit less than a third of my life, which is fairly significant. It doesn’t even quite belong to recent memory, and perhaps has escaped living memory into something quasi-zomboid. Part of the reason why this section is relatively short compared to the other ones is because I really don’t have a very good memory of what that was like, and it’s rather sad that my previous attempts never had long writeups regarding their potential and process (however, there do tend to be more little updates about the process).

Anyway, as it’s been such a long time, I’m trying to dig through old stuff to pick out exactly what I did back then. The first things I can find are somewhat easier and simpler problems, finding palindromes, or at least words which spell different words when reversed (I believe this was based on a program I had written a few years prior in Visual Basic). Another was for cracking hashes in a distributed manner.

Back then, I think those were one of the first explorations into the concept, of distributed computing in the browser. It was the days before WebWorkers and Cross-Origin Resource Sharing was in its infancy. The pool of possible computation was however, still large but most of it was forbidden. Take note, however that distributed and parallel computing have existed for far longer, perhaps even longer than the idea of a computer.

Computers get faster each year, thanks to Moore’s Law and more and more people get connected to the Internet each year. Perhaps in addition to Metcalfe’s law with regard to the value of a telecommunication’s network, is the ability to harness idle computation power in order to increase the vale of its participants linearly as the network grows. There are almost a billion people who are connected to the Internet, and however insignificant of a contribution each of those terminals brings to the network would add up into something truly remarkable.

However, hash cracking and palindrome finding are fairly trivial. They have little real world practicality and don’t seem in any way representative of the greater problems facing humanity. While it’s a little impractical to aim for some kind of project which has immediate applications to the value of humanity, it’s certainly a worthy target which is worth approximating. They’re isolated examples which are easy to parallelize and hardly count as real ventures into the field.

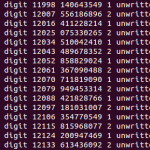

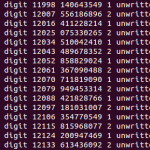

Calculating digits of pi is marginally less useless and represents something which is significantly harder and tasks which may be closer to the kinds of computations which are performed in the real world. There have been other projects with similar goals, most notably, PiHex, which acts as a sort of vindication of this as a possible legitimate attempt. At this point, I have no idea if the algorithm works with digits in the order of trillions, and that’s one of the big reasons I’m not actually trying to succeed PiHex.

Revisting

Okay, so I decided to dig this up again.

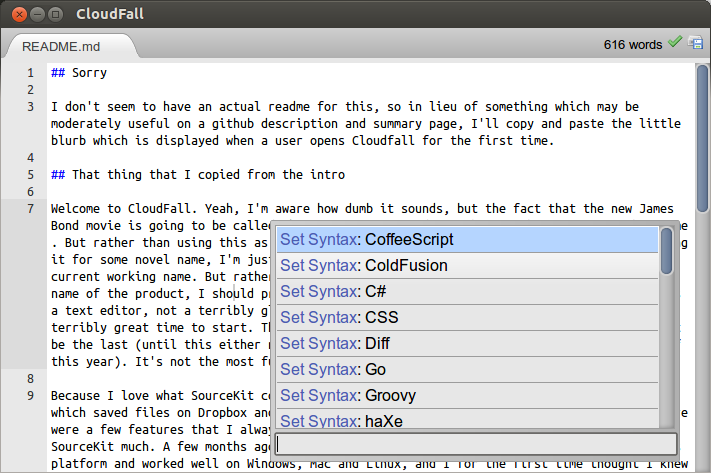

Why? Because I really want to play around with server-side JS a little more (just in case getting a node vps has anything to do with merit). The sort of funny thing is that’s exactly what it used to be, back in the ancient past, before NodeJS existed (it was before Google Chrome was released, and V8 wasn’t open source). I used to have an application which would schedule jobs for computation on the client and provide them in a more useful format.

However, I never bothered saving the files outside of the AppJet web IDE and the code was lost when the service was discontinued. I tried porting to Google App Engine, but that version was plagued with strange bugs which ended up printing out the wrong digits after a few thousand were computed.

Right now, revisiting the idea, I’ve added a few things which are somewhat more characteristic of the change in web browsers since my first attempt. The old version tried to mock threading by the liberal application of setTimeout, which meant that most interface interaction wouldn’t be terribly affected. However, it did incur a noticeable slowdown. Now, it uses WebWorkers, which provides numerous interesting possibilities. First and perhaps most important is context isolation and lightweight, asynchronous embedding in multiple domains (origins). Since WebWorkers can work (see what I did there?) across multiple origins and still have access to XMLHttpRequest, and the advent of Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS), it’s easy to embed this in a page. The low embedding overhead and the true multi-threading abilities bring a lot in the way of making this more than an intriguing concept and into something much more practical.

The code, which is now on the Github repository in a new folder named node has a very basic interface. Rather than manipulating the widths of divs for progress indicators, now it uses <progress> (it’s actually really cool to see how far the state of web platform’s state of affairs has changed over the past few years). One cool thing about the progress bar is that it guesses progress by dividing the current prime number by the end point, which has an interesting effect of making the progress bar faster towards the end (this happens because the distribution of prime numbers asymptotically declines). While I could possibly invert the effect in order to create a more linear progression fairly trivially, behavioral studies indicate that people who stare at progress bars all day feel less irritated (i.e. more satisfied) when the bar speeds up in the beginning and end (then again, the progress indicator isn’t really meant to be shown to people and if it is, the user experience is hardly something which is being optimized for, and this does nothing in the way of speeding up the beginning, in fact it’s quite the opposite by slowing down the beginning, so perhaps it should first linearize the progress and then map it to some function which as accelerated starts and ends, perhaps some trigonometric function).

Part of what is cool about the project is the underlying algorithm, a port of Fabrice Bellard’s optimized version of the Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe algorithm. Unique to the algorithm is that it uses up comparably little memory and as such it’s uniquely suited to distributed computing, especially in the browser environment which demands relatively thin clients (however, browser caching means that the download would only necessarily need to be completed once, and embedding the computation in an iframe with certain storage permissions and appCache could allow persistence). It’s a relatively short algorithm and fairly easy to port.

However, as it’s a digit extraction algorithm, it’s not very efficient for calculating digits sequentially. That actually is something of a feature which I neglected in the so-called modern incarnation. Older versions had the prime number (sub-job) allocation done on the server, which meant using up a lot of memory in keeping track of the jobs. The current one has a server which is entirely unaware of the actual computational process, which leads to being lighter persistence-wise but comes at the obvious cost of losing granularity in scheduling.

One optimization about this strategy is that a client doesn’t have to wait for a server to respond with another job request in order to continue. Instead, it operates in an almost completely asynchronous manner. On the client’s first request, the server gives it a job which is given by a starting point (a prime number to continue from) and a digit number. From that point, the client begins computing until that digit is complete, sending its progress back to the server once in every specified interval (a couple of seconds).

If the client was to disconnect in the middle of a computation (which can take quite some time, especially in later digits, so its more than certain to happen), the server will be able to resume the calculation by sending the request to another client after a certain expiration date has passed. So future refinements to the server (and possibly the client) could make it more efficient with processing digits of less significance by allocating jobs and taking into account certain checkpoints. For instance, all the prime numbers between 3 and some integer N have to be iterated through (where N is approximately 3 times the number of digits from the radix). Rather than maintaining a “single-threaded” system (as it currently does, the parallel processing power comes from sending out multiple digit segments to be processed), it could instead send out simultaneous requests for different segments. The client may have to be modified in order to stop at certain designated checkpoints to prevent clients from overlapping.

This sort of scheme would be more efficient than storing jobs used in previous versions, first of all by retaining the sort of “dumb” server which doesn’t do any real computation that contributes to the process. Instead it only acts as a mediator and persistence layer (as perhaps is the best role to give to any server). Rather than keeping track of every single prime number as a different row in some database, the server would only need to keep track of as many sections as clients exist.

The new version also has some interesting changes. First is the switch to NodeJS, which was hinted at before, since it acts as a persistent server rather than something which is called and disposed like a CGI process, the queuing system is now entirely in-memory. However, as soon as its possible, it writes out the completed digits into a file (pi.txt), and if the server is ever interrupted the computations resume from the last saved version of the digits (only the jobs which were processing during the shutdown are lost). However, this would need to be changed if it were to be some more ideal use of the digit extraction method, since in such a situation, the vast majority of jobs would be for a single span of digits (and it would really suck to lose all of those).

So in a sense, this update constitutes a regression, a step in the wrong direction in that it’s using the algorithm wrong. However, in another sense, it paves the way to a set up which has a few more ideal properties, a lighter weight server end and a more efficient use of computation time on the part of the clients. In essence, the shift from fixed sized discrete computational tasks (or jobs) to mere ranges. The obvious benefit to the latter is the reduced memory demand and the ability to operate continuously, i.e. without pausing for acquiring tasks and behaving truly asynchronously (in a very Node.JS style). Perhaps taking it further along this direction (since WebWorkers are allowed to access applicationCache), clients could be given a starting point and are just let to rip through a few hundred cycles, synchronizing less frequently. Some specialized data structures might be employed to keep track of individual contributions so that the ranges are doled out optimally. Maybe this should instead evolve into some kind of successor to the PiHex project rather than some incredibly slow and inefficient sequential pi calculation platform.

One thing which I didn’t explore was the concept of having a persistent socket to the server. For this set of circumstances, the benefits of maintaining a persistent bidirectional socket weren’t large enough to warrant that kind of development. Right now, it’s communicating through a few small GET requests to a server. Part of the reason GET was used rather than POST was that it was designed with the idea that it could theoretically run in a cross-domain manner, and sending a POST request requires preflighting with CORS headers. Since it’s only ever really sending 30 or so bytes at a time, any additional overhead should be avoided. But this itself is also perhaps an argument for using WebSockets (though certainly not long-polling, since that incurs even more overhead). Quite often the synchronization requests don’t require the server to give anything back, but HTTP-wise, the server’s always going to have to send about a hundred bytes of headers to fulfill the HTTP requirements. Also, whenever the server sends a request, it wastes about a third of a kilobyte with header information like the User-Agent. Network-wise it might in the end be more efficient just to have a low-overhead persistent socket connection.

Having a persistent socket would make synchronization interesting as well. While the changes wouldn’t be terribly drastic since there’s still the goal of minimizing transmission overhead, a few changes to the scheduling could be conveyed without necessarily waiting to the next checkpoint. And of course, there’s the trade-off which comes with the question of how long the checkpoints should be spaced. Right now, it’s something fairly low in the range of 10 seconds since the duration of a single page visit usually isn’t much more than a few seconds. However, if a client-side persistence layer is added, the checkpoints could be spaced out much wider. Perhaps instead of every few seconds, one could be made for every minute, hour, day or even week. Where a single computational task allocation could span multiple domains, multiple days and while the user is online and offline. However, having wider-spaced checkpoints does incur a cost in terms of synchronization. It reduces the operator’s sense of intimate awareness of what’s actually happening and increases the chance of overlaps.

Another possible step is some kind of framework which handles all of these problems automatically. Instead of having to manually manage variables and the synchronization of tasks between clients and servers, one could construct a domain specific language for distributed computing (a superset or subset of javascript which automatically manages the state of variables in loops and such to compile into some kind of client for generic parallelized algorithms). Maybe it’ll do something cool and look at which loop is the optimal one to split up based on the amount of data which needs to be sent across so that it could be minimized.

One of the things I played with while revisiting this project was playing with LLJS, another kind of specialized language which builds upon Javascript. As it’s marketed, the “bastard child of Javascript and C”, which manually manages memory. I was hoping that using a typed language might bring some speed improvements (not really, in this situation). However, LLJS might be a good basis for this auto-magical compiler for synchronous routines into largely parallelized code. However, maybe there are in fact limits to parallel computing, and it’s better to search for specific algorithms which have the right properties. And maybe in the end, the problem of porting it to Javascript and managing the client-server communication fades into a relative triviality.